Troubled times tend to spur interest in ways to foresee calamity before it occurs.

Genuine foresight requires methodical approaches like scenario planning to account for multiple variables and potential trajectories.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Economic Futures series applies scenario planning to some of the thorniest aspects of growth.

세계경제포럼, 2025년 7월 17일 게시

John Letzing

Digital Editor, Economics, World Economic Forum

“At some point we may get an odd quarter or two of negative growth.” So said the head of the UK’s central bank in early 2008.

A few months later, people watched in horror as the country’s economy descended into what’s now called the “Great Recession” – an era that’s taken a place of dishonor among other historical lowlights.

Just as previous periods of turbulence kicked up interest in better anticipating disruption before it inflicts serious damage, our current reality is encouraging a similar push. But any worthwhile effort likely won’t stop at fanciful prediction. It has to be a careful sorting of distinct, plausible scenarios grounded in present reality. Less soothsayer and more strategic analysis.

Worst-case economic planning is at least as old as the ancient Egyptian management of vital granaries that were the central banks of their day; predictions of barren fields had to be met with stockpiling, and a faulty projection of sufficiency could mean disaster. Successive prognosticators have often gotten it right over the years, but have also had some difficulty being heard. Just ask Ray Dalio, the high-profile investor credited with calling the last global financial crisis. Lately, he’s suggested people once again recognize the mechanical reasons for alarm.

Dire prediction alone may not be enough. Piecing together storylines that account for multiple trajectories can be more helpful. Recently, the World Economic Forum has started applying this in the form of scenario planning to some of the thorniest aspects of economic growth – in an increasingly complicated global context.

“Scenario planning has a long history, and at a time when dramatic disruptions to trading systems and long-established economic relationships are raising serious questions about what comes next, it has a particularly important role to play,” said Aengus Collins, the World Economic Forum’s Head of Economic Growth and Transformation.

The first edition of the Forum’s Global Economic Futures series applied scenario planning to productivity – an essential ingredient of growth that’s been in relatively short supply.

The four potential productivity scenarios projected for the year 2030 range from a “drought,” where simultaneous slowdowns in innovation and skills development undermine living standards and undercut most industries, to a “leap” where a virtuous circle of healthy innovation and skills-building generate tailwinds for just about every type of business.

They aren’t predictions, just guidance for decision-making.

The second edition of the series, published last month, zeroed in on competitiveness – a broad term with distinct meanings, depending on the context.

The four scenarios laid out for competitiveness in 2030 range from a “fortress economics” situation where protectionism and the weaponization of resources sap most industries, to a “fluid order” where geopolitical stability and reduced regulation spur dynamism and revive growth. At least, until the uneven distribution of benefits and lower safeguards start eroding prosperity.

Seeing scenarios, avoiding panic

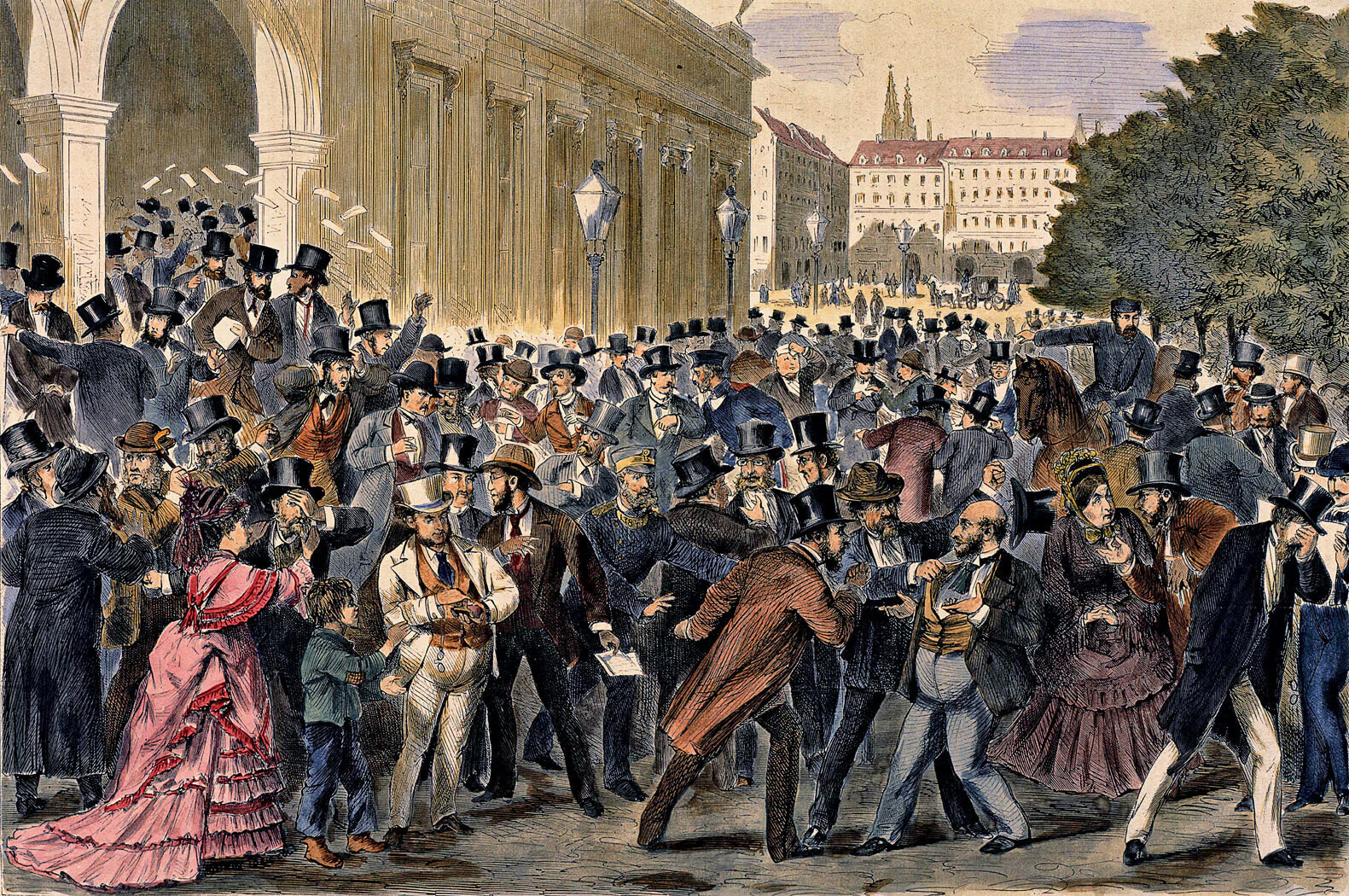

In 1873, just about everything seemed to go wrong all at once.

Investors on both sides of the Atlantic were pouring money into railroads and real estate at a heated clip. Only a few years earlier, the US had been laying about 2,000 miles of new railroad track annually, which surged to nearly 7,000 miles by 1872. When a real estate bubble in Vienna burst, it sent ripple effects westward through the British economy and Wall Street. Eventually a massive, overleveraged American bank went belly up, sowing panic.

Anyone keeping a close eye on the markets could’ve seen trouble coming. But when so much is riding on numbers going up, it can be tempting to put blinders on. Another case in point: the global financial crisis of 2008. Once more, rampant speculation in real estate ends in tears. A big Wall Street bank disappears. Rinse, repeat.

Ray Dalio and others may have seen the 2008 collapse coming, but there again many factors were working against clarity. Some of the same things undermining real stability for the financial system were creating an illusion of stability, and a lot of wealth, for a lot of people. The blinders were back on.

Scenario planning is a way of trying to take the blinders off.

The RAND Corporation grew out of a US military project to design an “experimental world-circling spaceship” in 1946. In the ensuing decades, it played a role in the early development of the internet and artificial intelligence. It also pioneered the use of modern scenario planning.

One of its most notable related efforts was to assess strings of events that just might lead to the start of a nuclear war.

More recently, it’s touted its use of scenario planning to do things like help Norway prioritize areas of research and innovation, and assist efforts in the UK to use technology to solve congestion problems.

Ideally, the process doesn’t just raise red flags – it helps people ask pertinent questions and explore possibilities that may not be readily apparent.

The Global Economic Futures work being done by the Forum is likewise designed to encourage critical and creative thinking, ultimately aimed at shaping better outcomes.

As a changing climate forces a broad rethink of economic policy, and geopolitical uncertainty mounts, there is no shortage of potential applications.