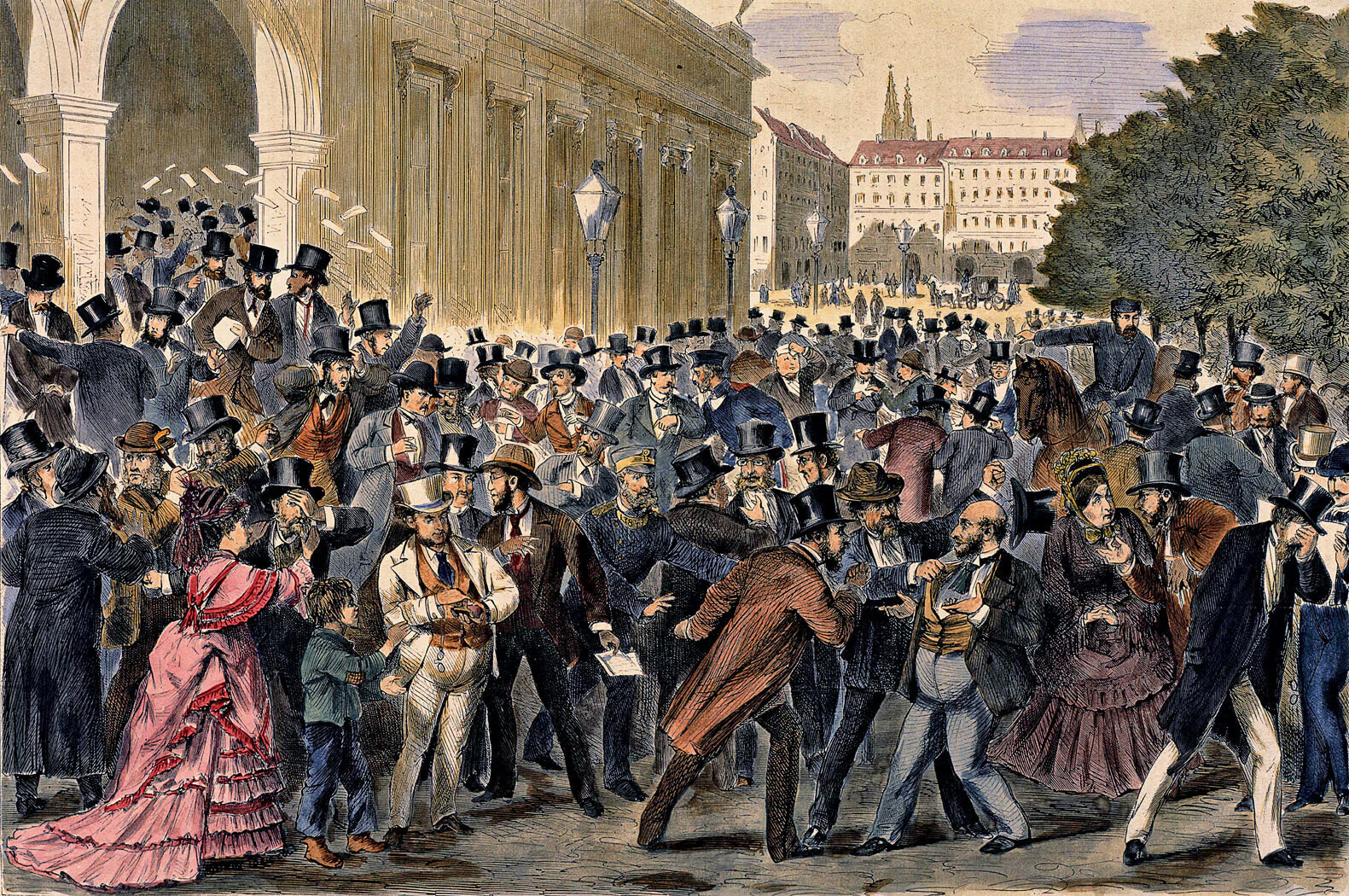

Global military spending spiked last year, drawing comparisons to the Cold War era.

Governments will almost certainly fund continued increases by ramping up borrowing, according to the World Economic Forum’s most recent Chief Economists Outlook.

That comes amid warnings that public debt is already hitting troubling levels. The wisdom in of much of the buildup will therefore rely on spending that can propel broader-based growth.

세계경제포럼, 2025년 5월 29일 게시

John Letzing

Digital Editor, Economics, World Economic Forum

Global military spending rose more sharply last year than at any point “at least” since the Cold War, according to a recent report. The world’s biggest economies have demonstrated zero desire to rein it in any time soon.

Their eagerness to splash out on defence comes as traditional alliances falter and perceived threats persist. Options available to fund these new outlays include raising taxes, or cutting back on other priorities. One of the more creative alternatives being floated is a rearmament bank, to pool financing for new weapons without necessarily busting government budgets.

But ultimately, much of the military buildup will rely on borrowing.

86% of the respondents surveyed for the Forum’s most recent Chief Economists Outlook think governments will increase public borrowing to move the needle on defence spending – compared with just 25% who see tax increases as likely.

The timing is less than ideal.

Global public debt is expected to rise by an additional 2.8% of GDP this year, according to a recent IMF assessment, putting it on track to hit 100% of GDP by the end of this decade. That would surpass its peak during COVID-19.

By way of context, it wasn’t so long ago that most countries saw the idea of matching the entirety of economic output with accumulated debt as deeply troubling (it’s since become far more common).

The cost of money is an aggravating factor; elevated interest rates have added significantly to public debt loads. In some ways, the recent global volatility induced by tariffs points to rate cuts. But it also creates upward pressure. If central bankers sense inflation creep as a result of the levies, they may try to contain it by holding the line or even raising rates.

The advanced economies sizing up bigger military budgets have fared better than others with increasingly pricey public debt, according to the IMF, but they’ll have to lay out a “credible plan” if they want to jack up defence spending under the present circumstances.

A euro on defence for 50 cents in GDP?

Europe contributed a big part of the global military spending increase in 2024. Its collective outlays rose by nearly a fifth when including Russia, which was in its third year of an invasion of Ukraine (a country that spent less than half of Russia’s total). Only a single European nation failed to bump up spending last year: Malta.

A major credit rating agency said in February that bigger deficits in a rearming Europe seemed inevitable, due not just to higher interest rates but also a concurrent need to financially support some of the world’s oldest populations. Allowing European Union governments to trigger escape clauses that permit them to blow past designated borrowing limits seemed necessary.

That’s exactly what a dozen countries requested several weeks later (more were expected to follow). One of them, Germany, disclosed recently that it’s on board with plans to raise military spending to 5% of GDP. It hasn’t come close to spending that much since the harrowing period immediately after the construction of the Berlin Wall, when it was still divided between East and West.

Have you read?

- Soaring public debt is worrying experts at Davos 2025. Here’s why most of us didn’t see it coming

- Can Europe fundamentally reshape its economies to focus on defence?

- Davos 2025: Special Address by Volodymyr Zelenskyy, President of Ukraine

Ballooning public debt is part of being on a war footing, which is where many countries feel they are now – whether actively engaged on battlefields or not. During World War II, debt nearly hit 150% of GDP in advanced economies. But industrial ramp-ups during conflict can also feed output that endures long after the last bullet is fired.

In the US, a mobilized economy shifted from churning out weapons to outfitting sprawling suburbs in the second half of the 20th century. At roughly the same time, Switzerland diversified a thriving armaments industry to supply things like office equipment and plastics to a rebuilding Europe. The Czech conglomerate Skoda, which had supplied arms to a wide variety of militaries, evolved into a maker of popular station wagons (“where were those cars even from?” wonders a character in a recent novel).

The escalation now anticipated for Europe is also projected to pay back in broader ways. One analysis suggested that every €100 it spends on defence could boost GDP by about €50. That is, if enough manufacturing is both domestic and focused on infrastructure.

Even if they want to shell out, countries can’t escape from fiscal reality. A separate analysis of military spending in the US warned that a dramatic increase there could ultimately do more harm than good, by turning “federal debt into a far more intractable problem.” (The US recently lost its last triple-A credit rating from a major agency, due to rising deficits, debt, and interest payments).

It’s a kind of growth that also comes with more specific caveats.

Long-term viability isn’t guaranteed. The need for concentrated military manufacturing comes and goes, which is a good thing overall but not optimal for places that rely on it. The greater Los Angeles area lost hundreds of thousands of defence-related jobs once the Cold War ended, spawning one of the more memorable anti-heroes in film history.

Other aspects can be equally problematic. The same Swiss armaments industry that flourished during World War II helped fund the acquisition of a collection now sitting in the country’s biggest art museum; the unsavory source of much of those funds has been one cause of well-documented controversy.

The best investments are those that help prevent the need for expanded militaries in the first place.

Barring that, more practical cooperation might be necessary. The EU appears to be making strides in at least one area: overcoming members’ longstanding reluctance to jointly issue debt, in a way that lightens the individual load for each. A region that initially united itself commercially in response to wars of the past seems poised to further strengthen that bond, to help confront whatever’s in store for its future.