Attempts to spare ourselves from excessive government spending with self-imposed debt rules tend to collide with reality.

As tariff-related upheaval mounts, these rules may come under even more intense pressure.

Ageing populations, lingering effects of the financial crisis and COVID-19, and security threats have already made significant public debt a fixture – though different ways of tracking it are possible.

세계경제포럼, 2025년 4월 4일 게시, 4월 7일 업데이트

John Letzing

Digital Editor, Economics, World Economic Forum

We’ve been through a lot. And we have the public debt to show for it.

A massive financial crisis upended economies, a pandemic warped reality, and a global order that once seemed secure started to feel a lot more fleeting – all while workforces continued to age out and retire at an unsettling rate. Now, a blitz of sweeping tariffs has suddenly made a global recession feasible. The self-imposed rules meant to limit the government borrowing needed to deal with all of this can feel like an exercise in futility.

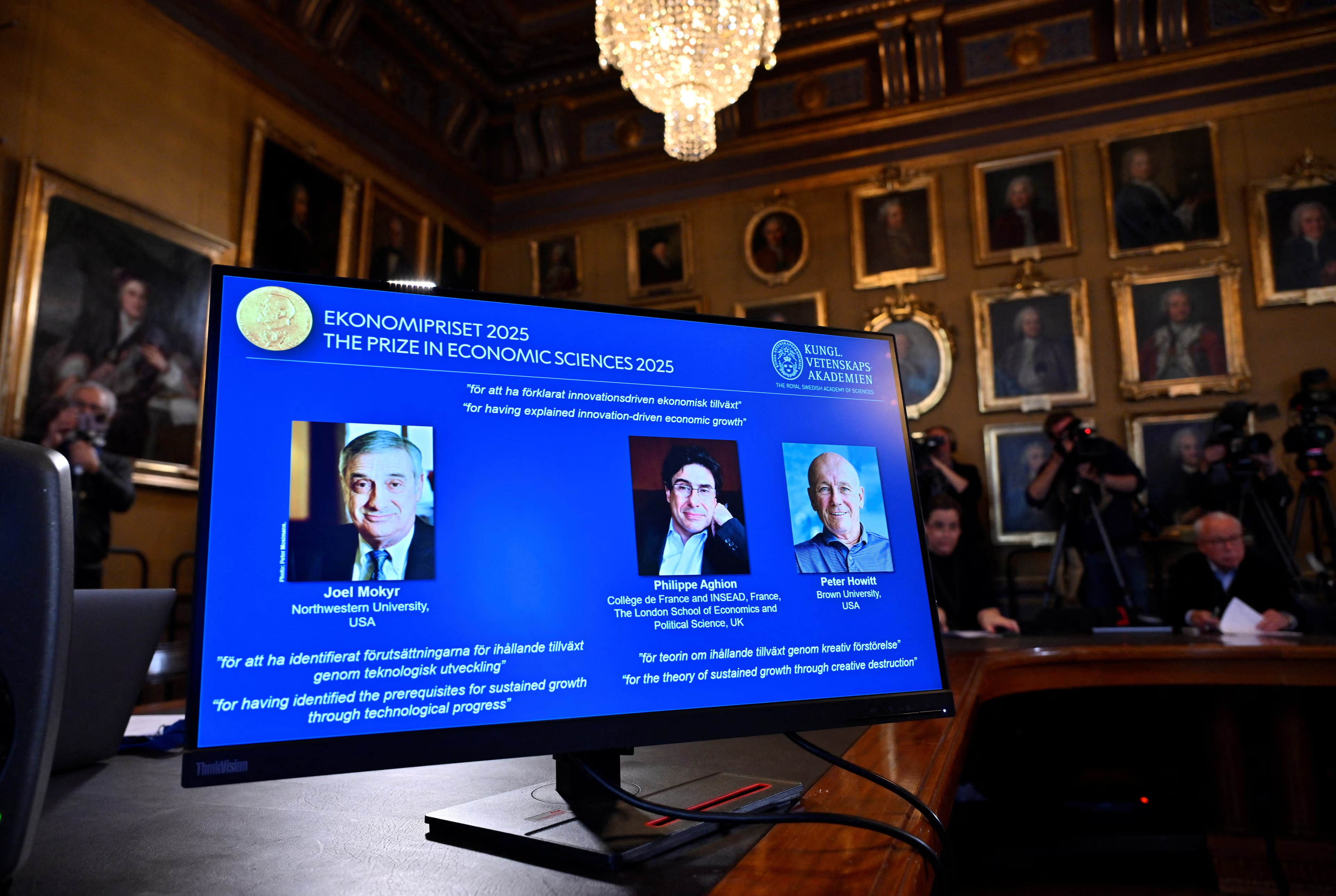

The world’s richest countries are expected to issue a record $17 trillion in bonds this year; less-wealthy economies tapped debt markets for more than $3 trillion last year alone. As a percentage of total economic output, public debt has been reaching levels not seen since people were picking up the pieces in the aftermath of World War II.

https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/22399828/embed?auto=1

Setting rules for public debt is an exercise meant to inject the right amount of anxiety into taxpayers expecting a continued return on their investment – in the form of a government able to keep paying its bills and providing services.

These rules may sometimes feel artificial, but the sense that we need protection from things veering dangerously out of balance, and limiting the resources available to keep roads paved, schools open, and the most vulnerable looked after, is very real.

The UK appears determined to stick to its rules adopted nearly three decades ago and solidified after the 2008 financial crisis, even after recently disclosing that a need for more heavy borrowing means likely having to cut disability payments. As recently as the 1990s, the country’s debt level was downright modest. Tumult in the decades since has prompted questions about whether rules meant to contain it can simply be changed.

That’s what the US does on a semi-regular basis. It’s not a rule there, it’s a debt “ceiling.” If breaking through seems inevitable, raise it; the country’s done that 78 times since 1960. Due to heavy borrowing and persistent deficits, a federal agency has said the ceiling may have to be raised yet again as soon as this summer.

Have you read?

- What is ‘financial repression’ – and should countries embrace it as debt climbs?

- Soaring public debt is worrying experts at Davos 2025. Here’s why most of us didn’t see it coming

- What’s a debt ceiling, anyway… and why does the US have one?

Australia scrapped its debt ceiling altogether not so long ago, though recent forecasts for greater public borrowing have stirred some interest in new official limits. And then there’s Germany.

One of the most striking aspects of Europe’s biggest economy has been its “debt brake,” enshrined in 2009 to severely restrict public spending (it has been noted that in the German language “debt” and “guilt” derive from the same word). Last month, German lawmakers decided that a pressing need to revamp the country’s economy and military necessitates finally easing off of the brake.

The right kind of ‘good, sound’ guardrails

Something widely shared by countries bumping up against self-imposed debt limits: age. Increasing numbers of people in these places who once paid into social protection systems as members of a workforce are transitioning into retirement and beyond. Europe’s population is expected to start declining roughly a decade from now. Last year, Italy introduced a new subsidy for the low-income elderly, as part of a €1 billion plan.

In Japan, the only country with a population older than Italy’s, costs related to supporting the elderly now account for about a third of public spending. Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio long ago surpassed 200%.

By 2022, the IMF counted 105 countries, or more than half, that had enacted at least one fiscal rule designed to curb government spending. “Good, sound” guardrails are essential for healthy growth, IMF First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath said recently on the Forum’s Meet the Leader podcast. The question is whether the right guardrails are in place for what’s being described as a high-debt, slow-growth world.

For a long time, governments borrowed a lot of money because they could. Interest rates were low, and money was cheap. But when central bankers decided more recently it was time to raise rates to fight inflation, borrowing got more expensive.

One reason rich countries are expected to issue so much new debt this year is to help pay off rising interest bills. For developing countries, the picture is bleaker – 17 of them, according to a recent estimate, are spending more than a fifth of their government revenue on interest payments.

https://flo.uri.sh/visualisation/22434518/embed?auto=1

In some places high public-debt levels are a feature, not necessarily a bug. Japan’s been able to maintain such extraordinarily high levels of gross debt because it’s kept interest rates low, its people and companies nonetheless buy up its relatively low-yielding debt, and it compensates by betting on high-return assets.

Singapore also maintains a remarkably high debt-to-GDP ratio, at well over 100%. But it’s deceptive. The city-state runs a balanced budget and typically enjoys relative fiscal abundance – it only maintains significant gross debt to do things like finance strategic infrastructure.

Which points to a fundamental truth: not all debt is bad. If it’s being used credibly to fund things vital for the future, it can be pretty good.

The same OECD report projecting record debt issuance by rich countries this year suggested that if governments alone have to do what’s necessary in advanced economies to transition to a low-carbon economy by borrowing, their debt-to-GDP ratios would rise by 25 percentage points in the next 25 years. Would that be considered bad debt that should trip alarms, or good debt? Does it merit its own kind of public-debt rule?

Some of the suggested ways to formulate more pragmatic and sustainable debt guardrails include decoupling them from the business cycle. Rules that remove some of the power of markets to determine what governments must pay in interest on their debt might also be worth exploring.

Vocabulary could also be addressed. “Debt” isn’t just a forbidding figure printed in black and white, or flashing on a doomsday-style clock. It’s a reflection of things needed to stay healthy, paid, and safe – from foreign military threats or a climate crisis.

Particularly now, it may benefit more people to factor shifting realities into reimagined rules governing these needs, instead of throwing up our hands and cutting back when they’re broken.