The US plans to apply a new tariff to copper imports starting next month.

That’s roiled the market for a metal already in short supply relative to rising demand – tied to everything from artificial intelligence to renewable energy.

Protectionist trade policy may not do much to address the issue of scarcity.

세계경제포럼, 2025년 7월 24일 게시

John Letzing

Digital Editor, Economics, World Economic Forum

An arid stretch of Arizona a few hours’ drive from the US-Mexico border is home to a copper mine so big that it has its own TripAdvisor reviews. “Needs to be seen to appreciate the scale,” one visitor marvelled. “Pretty dusty,” volunteered another.

Soon, it may have company.

Plans to dig America’s first significant new copper mine in more than a decade roughly 350 kilometers west of the massive facility in Morenci recently gained added impetus, when President Donald Trump promised to slap a 50% tariff on imports of the metal.

The offhand pledge to apply a copper levy by August 1 jolted markets. Futures contracts, which are agreements to buy it at a predetermined price, hit a new record. Traders scrambled to redirect as many shipping containers full of it as possible back to the US before a tariff is enacted, pocketing large sums in the process. Chile, a country that relies on copper for the bulk of its exports, said it was eager to hear more about the policy – and quickly.

Have you read?

The current US administration has by now targeted a lot of things with tariffs, which are added taxes on goods American companies want to import. That includes aluminum and steel. But copper just might be the metal most essential for a modern economy, and we don’t seem to have enough of it.

The billions of smartphones now sold every year rely on it. Demand among carmakers is expected to triple by 2030 as they shift to electric, and it’s a fundamental part of renewable-energy infrastructure. The AI bubble is creating even more appetite; the addition of a single data center needed to train new models can require 27 metric tons of the metal, equivalent to a fully loaded fire truck.

“Copper is essential to both the energy and digital transitions, and supply was already under pressure even before the emergence of potential trade barriers,” said Alan González Morales, the World Economic Forum’s Lead, Nature Positive Industries – Mining. “The industry is innovating, from new extraction methods to circular business models, but we need to accelerate progress to meet rising demand and ensure sustainable operations.”

The mere prospect of a US copper tariff had already triggered shortages in Europe, where Poland is a major supplier (European Union imports from Russia have been officially banned as part of sanctions applied after its invasion of Ukraine). When the policy was finally announced, Latin America, home to many of the biggest mining operations in the world, went on high alert.

The US relies on imports for slightly less than half of its consumption of refined copper, which it gets mostly from Chile, Canada, and Mexico. That’s far less than its 95% reliance on imports for rare earths (the metallic elements vital for everything from jet engines to semiconductors) – but not minimal enough to skirt similar calls for greater self-sufficiency.

There are other parallels between America’s relationships with copper and rare earths. In both cases, the US has a relative abundance sitting in the ground, but less capacity than other places to dig it out and process it. And the country was the world’s biggest producer of each before being surpassed in the second half of the 20th century.

Have you read?

China, which has accounted for well over half of global copper imports in recent years, is also trying to gain more self-reliance. Its production has been expected to more than quadruple between 2010 and 2028, and its companies are already estimated to control 80% of the output in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Yet, it’s unclear if any country’s efforts will be enough. The International Energy Agency recently warned that global copper demand may outstrip supply within a decade.

Car batteries, wind turbines and ‘Zamrock’

The development of copper tools enabled civilization to emerge more than seven millennia ago. Bets are being made that the metal could now help civilization endure, by reducing its carbon footprint.

Copper plays a foundational role in the clean-energy transition. The electrification of power grids and industrial equipment require it, and so do the batteries propelling electric cars. A single wind turbine can contain more than four metric tons.

The UN says 80 new copper mines may be necessary in the next half-decade to supply everything we’ll need, and it has called for more copper recycling efforts. It has also warned that copper-dependency can make an economy particularly vulnerable to things like trade restrictions.

Zambia has plentiful reserves and a long history with the metal. It’s now the biggest exporter of raw copper in the world. One of its cultural exports, a hybrid of traditional music and psychedelic rock (“Zamrock”), originated at social clubs built for miners – and waned when declining copper prices exacted a heavy economic toll. The CEO of a company expanding extraction efforts in the country said recently he’s confident the volatility created by tariffs won’t dilute long-term demand.

The US has its own history with copper. An area of the Upper Midwest is still called Copper Country, though its last industrial mine closed a few decades ago (leaving behind a problematic environmental legacy). Operations in Arizona have also waxed and waned; a temporary shutdown of the Morenci mine amid flagging copper prices in the early 1980s sent the local unemployment rate to 58%. Subsequent decades saw the discovery of new deposits and expansion.

Expansion of the Morenci copper mine in Arizona from 1984 to 2022.Image: EarthTime

Production is just a single part of a complicated global supply chain.

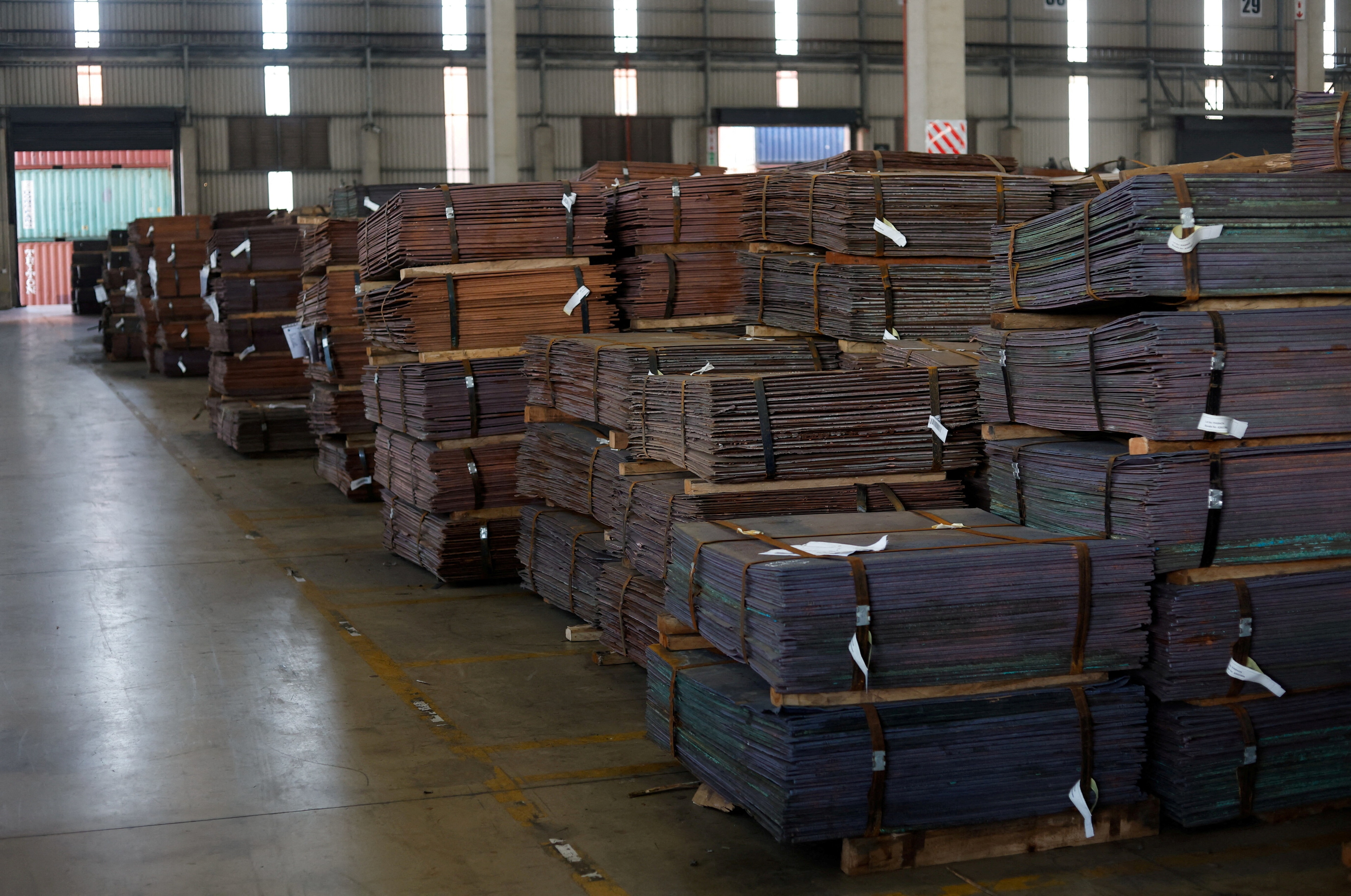

The US has been one of the fastest-growing markets for Zambia’s raw copper, but its biggest importer by far is Switzerland. Companies based in the landlocked country do the testing, processing, and paperwork required to effectively transition a hunk of metal into the international marketplace. Zambian copper likely never actually crosses the Swiss border, and is instead sold in transit from bonded warehouses.

Raw copper from Zambia awaits export in a South African warehouse.Image: REUTERS/Rogan Ward

And then there are the thieves. Copper looting tends to rise in tandem with prices. In one recent case, 600 meters of cable were stripped from the Eurostar rail line connecting the UK to continental Europe. It’s an illegitimate signal of legitimate demand.

That demand has compelled efforts to seek out copper in places no one is ever likely to see with their own eyes, much less write a TripAdvisor review for. Potential mining efforts on the ocean floor would be done with unmanned machines, and not without controversy.

The spectre of a US copper tariff has caused anxiety, though that’s in keeping with the fallout from other dramatic trade announcements in recent months. Until August, details will likely remain sparse.

There can be a dissonance between stories like this one, about short-term drama triggered by tariffs, and a relatively undisturbed global economy. Businesses are able to find hedges, and producers reroute. The reality is that not all countries are equally affected.

But when it comes to copper, globally shared issues of sustainability and scarcity will likely transcend any single trade policy.