The European Union has opted to push back against tariffs imposed by the US, a traditionally vital trading partner.

But it’s also sought to negotiate in the face of the US’s paused ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs and other levies.

It’s a balancing act that looks beyond basic economics to navigate a disorienting period.

세계경제포럼, 2025년 4월 11일 게시

John Letzing

Digital Editor, Economics, World Economic Forum

“Liberation Day” once had an unambiguously positive meaning in the context of Europe’s ties to the US.

Now, “liberation” has the ring of a warning shot. As in, potential liberation from mostly frictionless access to a market that happily consumed more than a half-trillion dollars worth of European Union goods like medicines, cars, and wine last year alone.

The EU recently joined most of the rest of the world in being targeted by US “reciprocal” tariffs (20% in the EU’s case). The bulk of those “Liberation Day” measures may be on a 90-day pause at the moment, but the message was sent. In the meantime, Europe must still account for other US tariffs applied to its steel, aluminium and cars.

Europe will define for itself what “liberation” means now. So far, the EU appears to be maintaining a delicate balancing act that goes beyond basic economics to take into account practical political realities. Retaliation plays a part, but so does negotiation – and keeping a steady eye to a future potentially less clouded in chaos.

“The EU’s setup makes it uniquely well-positioned to manage a tariff war,” said Andrew Caruana Galizia, the World Economic Forum’s Head of Europe and Eurasia. “It has an extremely competent trade bureaucracy with the power to negotiate on behalf of the entire bloc, and it can take far-reaching countermeasures without unanimity among its 27 member states. This means it tends to react both swiftly and calmly on trade matters, which is exactly what we’ve seen in this latest round.”

Earlier this week, EU member states approved countermeasures targeting a broad range of American goods, from yachts to chickens, in response to the US tariffs applied to steel and aluminum.

The list of targeted goods was broad, but also reflected a lingering hope that the fallout can be contained; American bourbon got a pass, for example, to spare the EU’s bountiful wine and spirits exports headed in the opposite direction. This list, too, was later put on hold to focus on negotiations.

Have you read?

- How do tariffs work – and do they work?

- How impacted is your country by the Trump tariffs?

- Trump tariffs: Visualising new US trade restrictions

Eventually, EU strategy could involve sidestepping US-related drama and doubling down on a consumer market in China that’s far less wealthy at the moment, but making progress.

EU-China trade relations have had their own complications. Though on balance, they may be relatively less distracting and hopefully not as destructive.

President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs are based on trade deficits, or the difference between what countries currently buy from the US and what they’re able to sell there. For the EU, that was nearly $236 billion last year.

Economists have questioned the logic of this approach; deficits can just as easily result from supply chain realities as iniquity (factoring Europe’s value-added taxes into tariff considerations has also drawn disagreement).

True, the average economist might also counsel against “reinforcing the carnage” by retaliating against tariffs. But for the EU, more is at stake than simple economic common sense.

Playing the long game, maintaining negotiations

“This is a problem Americans really have, we tend to not think of other countries as real,” the economist Paul Krugman said during a recent interview. Krugman may be unique among his peers when it comes to tit-for-tat tariffs. “There’s a pretty good case for retaliatory stuff,” he said, if only for the political purpose of maintaining national pride.

Romantic ideas about national belonging originated in Europe, after all.

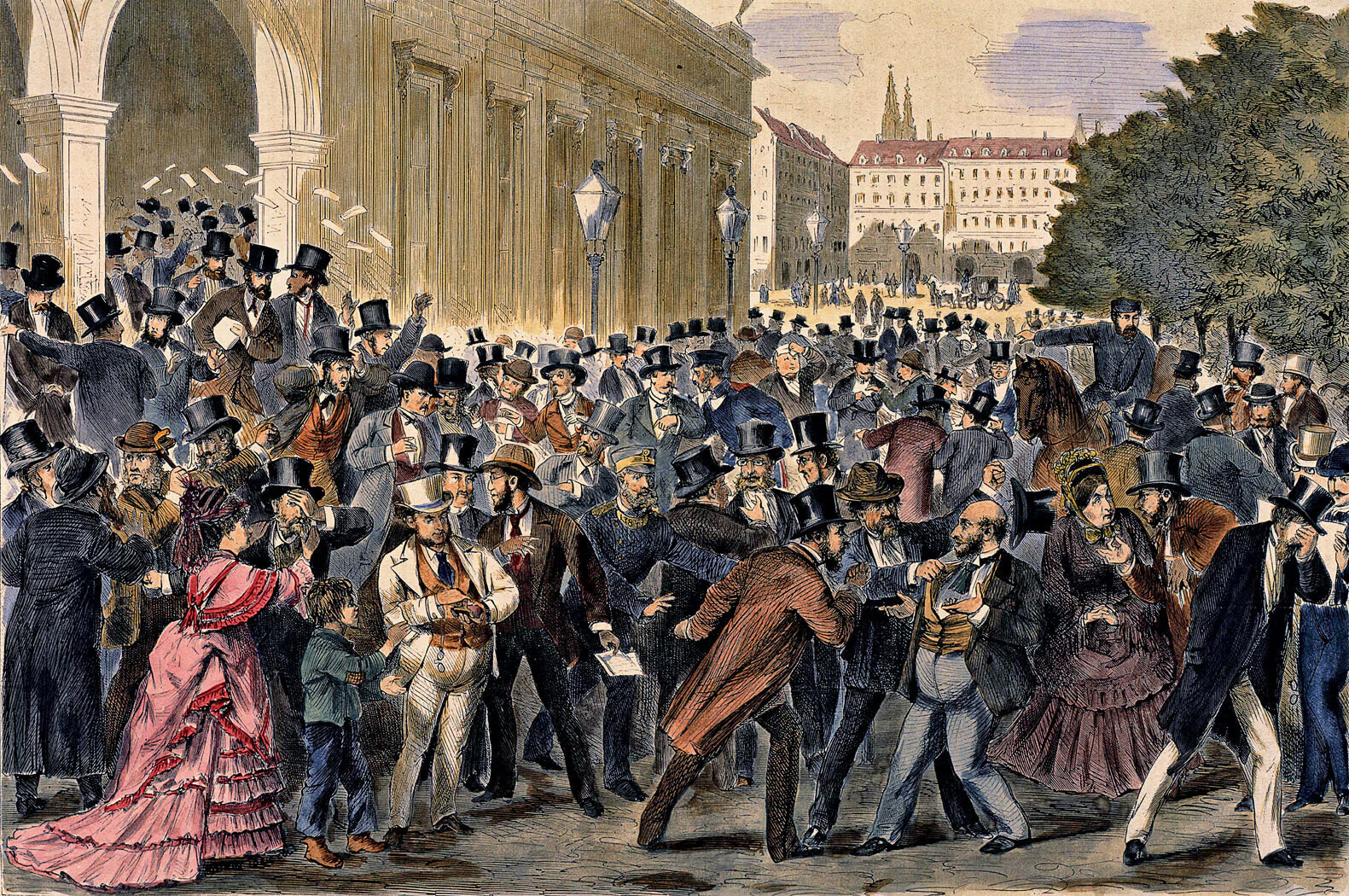

And, Europe is no stranger to trans-Atlantic trade confrontation. A flood of relatively cheap agricultural imports from the US in the late 19th century, memorialized as the European grain invasion, triggered a wave of tariffs.

Europe is also familiar with dramatic experiments in economic renewal forced on it by world powers, heavy on retribution for perceived slights. The brutal Soviet remake of economies in countries like Czechoslovakia and Hungary during the Cold War would require decades to undo.

Europe’s biggest economy seemed as of recently to be on the cusp of a reinvention of its own; lawmakers in Germany agreed to overhaul its strict debt rules, drawing the renewed interest of foreign investors. As the specter of US tariffs loomed larger, however, talk turned to economic contraction.

Even before the severity of threatened and actual US tariffs crystalized, Europe was nurturing other relationships. A trip by the head of the European Commission to India in February was followed by news earlier this week of an imminent free trade agreement. There have also been signs of a potential rapprochement with China, and the EU is expecting to host a summit for dignitaries from Beijing in July.

But compensating for tariffs that wrench Europe away from the US market would be a monumental task.

As it plays the long game, the EU can take into full account that a genuine effort is underway to fundamentally rewire the global economy in a manner that favors the US, while still calmly calculating how to best respond.

Experts say that following the prompts implied in the tariffs, by building new factories in the US that employ Americans to supply Americans with goods, would be a long and costly process with uncertain outcomes.

Instead, a mix of patience and negotiation is more likely, at least until there’s greater clarity on what this particular global rewiring will look like. As with other pressing matters, it will require that EU members maintain sufficient unity.

Because even at a time of great uncertainty, some things still seem certain at least for the foreseeable future. Midterm congressional elections in the US next year that could shift the balance of power, for example, and a presidential election slated for 2028 – at roughly the same time European investments made now in new US factories would be coming online.